Survey on climate education - Results

In addition to pupil-organised climate marches in 2019, climate education has gained significant attention in Europe and around the globe. Although Italy remains the only EU country to have made climate change education compulsory in schools, we are seeing initiatives like the Environmental Action Programme (EAP) in Sweden, UNESCO’s climate change education, and the eTwinning community doing their part to raise awareness and provide opportunities and resources.

Teachers can play a vital role in empowering young people to develop their understanding and attitudes when it comes to climate education. However, this can be a challenging topic for them to address in their classrooms, whether because of its controversial nature, the lack of understanding they may have themselves on the issue, or the lack of connection they may see with their own subject matter.

The survey ran from 11 May to 21 June 2020 and attracted 1101 responses – of whom 89% are teachers or head teachers – from 36 countries, mostly Spain, Turkey and Romania.

Results (N=1101)

1. In your opinion, are schools in your region equipping students with the knowledge and skills to understand climate change and take appropriate action in their own lives?

Almost all respondents agreed that climate education is a school’s responsibility. However, 70% agreed that the curriculum does not sufficiently address climate education, and only 29% felt that climate education is already sufficiently covered in the school curriculum.

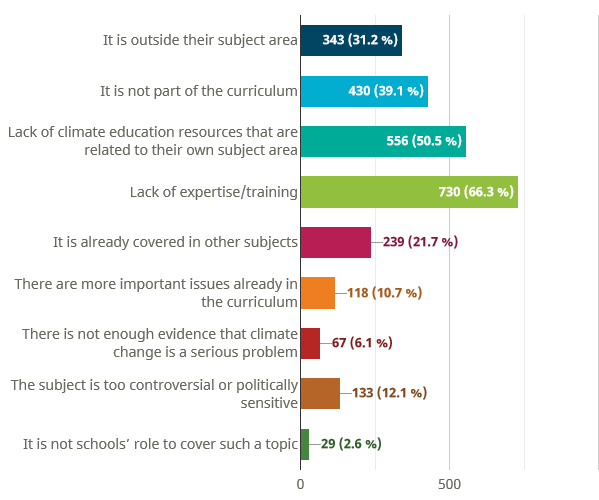

2. In your opinion, what are the main reasons why teachers in your school or region might not include climate education in their lessons? Choose all that apply.

Lack of expertise or training was the most common reason (66%) why teachers might not include climate education in their lessons, followed by a lack of climate education resources (51%). This is in line with similar surveys in Canada and the UK, in which 3 out of 4 teachers reported lacking adequate training in climate education.

For almost 39% of respondents, climate education is not part of the curriculum, and for 31%, it is outside their subject area. A further 12% felt that the topic is too controversial or politically sensitive, while 11% said there are more important issues that the curriculum prioritises. A smaller percentage (6%) were sceptical about climate education as a whole, arguing that there is not enough evidence that climate change is a serious problem.

3. Thinking of your school, or a school you know, what would be its reaction to pupils taking climate change into their own hands (e.g. ad hoc meetings, social media campaigns, direct action, climate strikes)?

A large share of respondents said their school would provide support for pupils actively engaging in climate change campaigns (39%), or reported that the school would leave it up to the teacher to decide what position to take (38%). Other respondents (11%) claimed that the school would remain neutral. Fewer than 4% thought their school would disapprove of pupils’ organising actions such as awareness-raising campaigns and marches.

4. To what extent do you agree with the following statements?

Strongly disagree

Disagree

No opinion

Agree

Strongly agree

Opinions were split on whether teachers have the necessary knowledge and resources to teach climate education, with 45% disagreeing or strongly disagreeing with this claim and 42% taking the opposite stance. Over 90% of respondents strongly agreed or agreed that climate education can be easily integrated into subjects outside the sciences and geography. Only around 35% of respondents strongly agreed or agreed that their curriculum covered all topics related to climate change. Finally, around 60% of respondents agreed that the curriculum includes the opportunity to debate climate change action as well as the facts about the environment. Taken together, respondents seem to agree that the topic has an interdisciplinary nature that would involve multiple subjects and debate.

5. What do you think the attitude will be towards climate education in the next two years?

Not important: learning about other crises, such as wars and global pandemics, should be prioritised over climate change in school education

Neutral: it is something to think about alongside other societal issues

Important: they will see it as a serious issue to discuss and learn about at school

According to 61% of respondents, school education authorities view climate education as a serious issue to discuss and learn about at school. This attitude is shared and amplified by teachers and school leaders (71%), as well as pupils (73%). However, many predict the attitude towards climate change will be neutral or that it is less important compared with other global issues, including pandemics (39% hold this view for school education authorities, 29% for teachers and school leaders, and 28% for pupils).

Conclusions

Learning about the causes of global warming is already recognised by the TIMMS science framework as an essential part of science education. Furthermore, researchers strongly suggest that climate change should not only be taught in science classes, as it is a complex topic lending itself to critical thinking. Research shows that instead of provoking detached negative reactions, education can increase engagement by focusing on hope and through narrative and storytelling.

The results of our survey reflect this complexity of climate education. More than half of the respondents think that their school curriculum does not sufficiently address the topic and that they need more training and support in teaching it. Although a large proportion of respondents agreed that schools should address the topic more and that it can easily be integrated into subjects outside the sciences and geography, others considered the topic politically sensitive and not scientifically sound. 77% of respondents agreed that schools or individual teachers would support pupils who take action, while around 11% would stay neutral.